Naniwa Bridge, Lovingly Known as the “Lion Bridge”

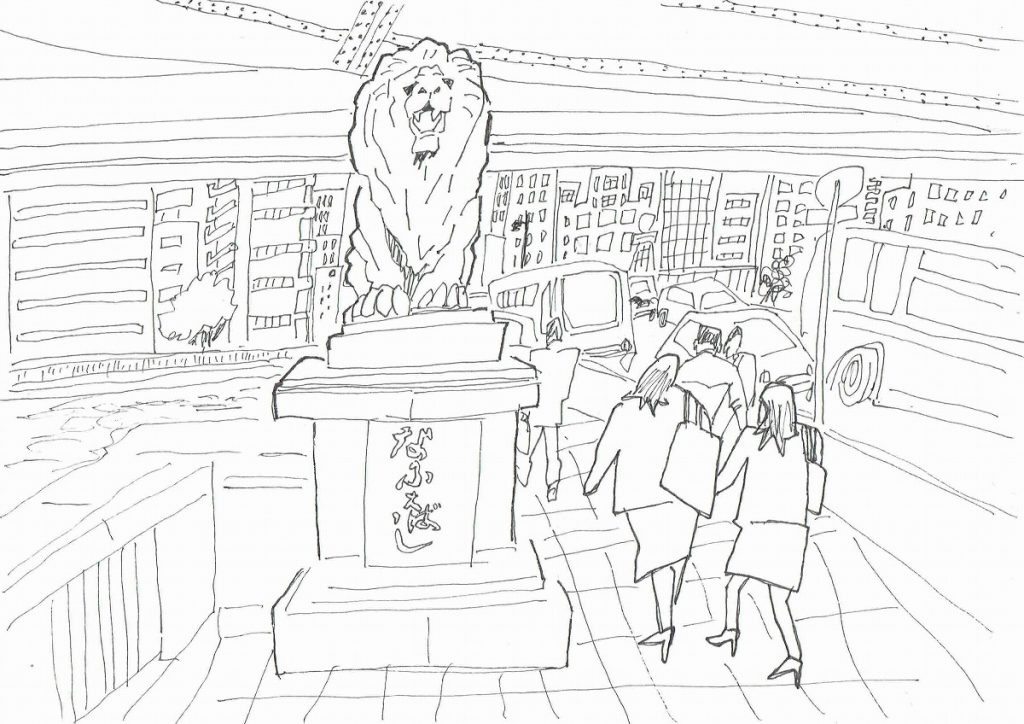

The Lion of Naniwa Bridge (Naniwabashi)

Illustration by Hiroki Fujimoto

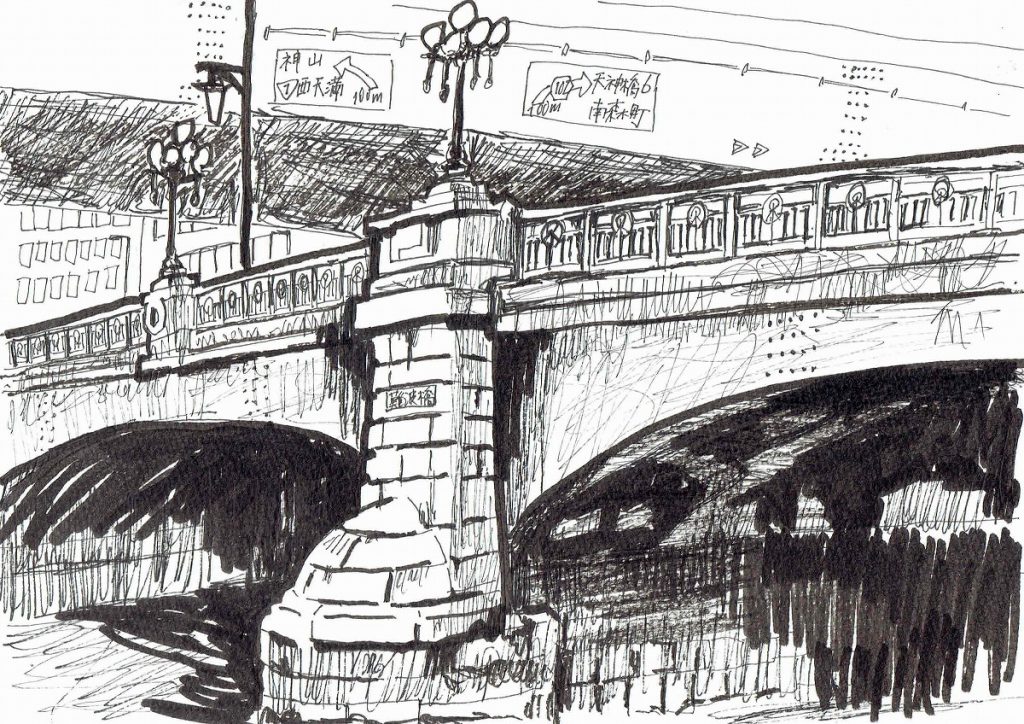

Naniwa Bridge (Naniwabashi) [Osaka City, Kita & Chuo Wards]

The Lion of Naniwa Bridge (Photo Taken in September 2021)

Contents

- 1 Naniwa Bridge (Naniwabashi): One of the Three Great Bridges of Osaka

- 2 Ancient Naniwa Bridge

- 3 Naniwa Bridge in the Edo Period

- 4 Naniwa Bridge After the Meiji Era

- 5 The Present-Day Naniwa Bridge

- 6 Overview of Naniwa Bridge (Naniwabashi)

- 7 Overview of Naniwa Bridge (Naniwabashi)

- 8 Conclusion

- 9 Naniwa Bridge Overview

Naniwa Bridge (Naniwabashi): One of the Three Great Bridges of Osaka

From upstream on the Okawa River, the bridges are arranged in order: Tenma Bridge, Tenjin Bridge at the easternmost tip of Nakanoshima, and Naniwa Bridge. As one of the Three Great Bridges of Naniwa, which played a crucial role in Osaka’s transportation, Naniwa Bridge was also a Kōgi-bashi—a public bridge maintained and constructed under the jurisdiction of the Edo Shogunate.

Ancient Naniwa Bridge

The exact origins of the construction of Naniwa Bridge remain unclear. Historical records, such as the Genkō Shakusho (a Buddhist historical text), indicate that the bridge was built by Gyōki in Tenpyō 17 (745) during the Nara period. However, the authenticity of this claim is uncertain.

In ancient times, bridge construction was often led by Buddhist monks dedicated to spreading their teachings among the people. In Osaka, numerous legends surround Gyōki’s involvement in bridge building. Born in Izumi Province (present-day southern Osaka Prefecture), Gyōki studied at Yakushi-ji, the head temple of the Hossō school of Buddhism. Beyond his religious teachings, he also devoted himself to social projects, including temple construction, bridge building, and embankment development. His many achievements have inspired various legends, and it is believed that the records of Naniwa Bridge’s construction may be one such account linked to his legacy.

Naniwa Bridge in the Edo Period

The existence of Naniwa Bridge became more defined when it was officially recognized as a Kōgi-bashi (a public bridge under the jurisdiction of the Edo shogunate) at the beginning of the Edo period.

The Ōkawa River splits into two branches—Dōjima River and Tosabori River—at Nakanoshima. Today, Naniwa Bridge consists of two separate bridges spanning these two rivers. However, during the Edo period, Nakanoshima’s geography was different, and the point where the Ōkawa split into two streams was located further west. As a result, the Naniwa Bridge of that time was a single, long bridge crossing the wide Ōkawa River. After the Yodogawa flood control project in Jōkyō 1 (1684), the bridge’s length extended to over 230 meters.

The arch of Tenjin Bridge had a steep gradient of 1 jō 4 shaku 5 sun (about 4.5 meters), while Naniwa Bridge’s arch measured 1 jō 2 shaku 5 sun (3.8 meters), also quite steep. This design was intentional to accommodate boat traffic. Some believe the steep incline was also meant to limit the use of carts, which could damage the bridge and complicate maintenance. Similar concerns about bridge preservation were recorded for Tenjin Bridge as well.

The area around Naniwa Bridge was lined with storehouses owned by feudal domains, making it a bustling hub of people, horses, and boats. The lively commerce and transportation must have given the town a vibrant atmosphere.

At the same time, this area was also a popular leisure spot. During summer evenings, people would gather along the banks of the Ōkawa River to enjoy the cool breeze, and many would take part in boat rides. Classic Kamigata Rakugo (Osaka-style comic storytelling) pieces like “Yūzanbune” and “Funabenkei” depict lively interactions between people enjoying the breeze on the bridge and those riding boats. The riverside would be filled with food stalls, creating a lively festival-like scene.

Additionally, Naniwa Bridge was a prime location for cherry blossom and moon viewing, as well as fireworks displays, attracting large crowds. The Settsu Meisho Zue Taisei (Illustrated Guide to Famous Places in Settsu) describes the breathtaking view from the bridge:

“From this bridge, the east-west panorama is spectacular. Looking around, more than ten bridges can be seen at once, offering an unparalleled scenic view of Naniwa.”

This suggests that in the Edo period, Naniwa Bridge was not just an essential transportation link but also a place of great beauty and cultural significance.

Naniwa Bridge After the Meiji Era

In Meiji 9 (1876), Naniwa Bridge was converted into an iron bridge. During this reconstruction, the eastern tip of Nakanoshima was extended, transforming the original single wooden bridge spanning the Ōkawa River into two separate bridges crossing the Dōjima and Tosabori Rivers. The first section to be converted into an iron bridge was the northern span over the Dōjima River.

Interestingly, the newly extended tip of Nakanoshima was landscaped with trees and flowers, becoming what is now known as Nakanoshima Park, marking the beginning of one of Osaka’s most famous urban green spaces.

The Great Flood of 1885 and the Temporary Boat Bridge

In Meiji 18 (1885), a catastrophic flood destroyed the southern section of Naniwa Bridge, which was still made of wood at the time. The floodwaters swept away upstream bridges, including Tenma Bridge and Tenjin Bridge, and their wreckage crashed into Naniwa Bridge, causing about four ken (approximately 7.2 meters) of the structure to collapse instantly.

As a result, all bridges connecting Senba to Nakanoshima were lost, cutting off a vital route for transportation. Although ferries were set up at two or three locations, they were insufficient to handle the heavy flow of people. To address this, authorities decided to build a temporary boat bridge at the site of Naniwa Bridge.

A boat bridge consists of multiple boats lined up and connected, with wooden planks placed over them to form a passable structure. At Naniwa Bridge, over twenty merchant boats (uniga-fune, used for loading and unloading cargo) were linked together with logs, and cedar planks were laid across them to form a bridge. While procuring the boats took some time, the actual construction of the bridge was completed in just four hours, demonstrating remarkable efficiency.

The boat bridge was set up on July 7, five days after the flood struck. However, as the construction of a temporary wooden bridge progressed, the boat bridge was removed on July 14, lasting only about a week.

The Full Iron Bridge Conversion in 1886

The following year, in Meiji 19 (1886), the southern section of Naniwa Bridge was also converted into an iron bridge. However, it was not a fully iron structure at this stage—only the bridge piers were made of iron. Compared to Tenma Bridge and Tenjin Bridge, which were completely rebuilt with imported iron materials, Naniwa Bridge may have seemed somewhat less impressive in appearance.

The Present-Day Naniwa Bridge

Naniwa Bridge took on its current form in Taishō 4 (1915) as part of the city’s tramway expansion project.

難波橋(大正4年完成)

The Sakai-suji Line, planned as part of the third phase of the city’s tram network, opened in Meiji 45 (1912), running from Ōebashi Minamizume to Nipponbashi 3-chome. However, the road widening required for the tram’s construction met with strong opposition from local residents. The dispute extended beyond Sakai-suji, involving neighboring streets and businesses in a heated debate.

Ultimately, a compromise was reached, allowing the tramway to be built along Sakai-suji. When the city decided to extend the line across the Ōkawa River to Tenjinbashi 6-chome, it was also determined that the tram would continue along Sakai-suji.

As a result of this decision, Naniwa Bridge, which had previously stood one block west of Sakai-suji, was relocated and rebuilt along Sakai-suji, aligning with the new tram route.

Naniwa Bridge in the Taishō Era (From the Osaka City Library Collection)

Meanwhile, the development of Nakanoshima Park was progressing, adding another layer of significance to the reconstruction of Naniwa Bridge. Rather than serving purely as a transportation infrastructure, the bridge was also designed to enhance the aesthetics of the park.

To reflect this dual purpose, decorative elements were incorporated into the design. The bridge’s parapets were engraved with the Osaka city emblem, while the substructure and lampposts featured elaborate ornamentation. Additionally, a grand stone staircase was built, allowing pedestrians to descend seamlessly into the park.

The opening ceremony of the new Naniwa Bridge was conducted with great solemnity. Following the formal proceedings, the celebration transformed into a lively festival, complete with traditional dances and fireworks, drawing large crowds.

Among the many ornamental features of Naniwa Bridge, the lion statues stand out as the most iconic. Sitting atop the main pillars bearing the bridge’s name, these stone lions are positioned as a pair, following the traditional A-un (open-mouthed and closed-mouthed) formation, symbolizing protection and strength.

The Lion of Naniwa Bridge (Photo Taken in September 2021)

The Lion of Naniwa Bridge (Photo Taken in September 2021)

The lion statues of Naniwa Bridge, sculpted by Kin’ichi Amaoka, stand 3.5 meters tall and weigh a massive 18 tons, exuding an impressive and dignified presence.

Traditionally, in A-un (open-mouthed and closed-mouthed) formations, such as shrine guardian dogs (komainu), the A-gyō (open mouth) figure is placed on the right, while the Un-gyō (closed mouth) figure is positioned on the left. However, on Naniwa Bridge, this arrangement is reversed—though the reason remains unknown.

Today, these lion statues remain an iconic symbol of Naniwa Bridge, giving it the affectionate nickname “Lion Bridge” (Raionbashi).

Interestingly, while there are four lion statues on the bridge (one pair at the north end and another at the south end), there is a fifth lion—located in Wakayama. This statue was reportedly placed in the garden of a mansion built by Isuke Matsui, a wealthy merchant originally from Wakayama who made his fortune in Kitahama, Osaka. However, how Matsui obtained the lion statue remains a mystery.

Preservation and Restoration Efforts

- In Shōwa 47 (1972), major restoration work was carried out on Naniwa Bridge. Special attention was given to preserving its original appearance, ensuring that its historical integrity was maintained.

- In Shōwa 60 (1985), the bronze lampposts, which had been lost during wartime, were restored. These ornate lampposts add a retro charm to the bridge, preserving its classical elegance.

Illustration by Hiroki Fujimoto

Overview of Naniwa Bridge (Naniwabashi)

難波橋と北浜駅(2021年9月撮影)

Overview of Naniwa Bridge (Naniwabashi)

Basic Information

- Name: Naniwa Bridge (Naniwabashi)

- Nickname: Lion Bridge (Raionbashi)

- Location: Kita & Chuo Wards, Osaka City

- Crosses: Dōjima River and Tosabori River (Ōkawa River system)

- Construction: Originally a wooden bridge, later rebuilt as an iron bridge in 1876, and reconstructed in its current form in 1915

- Current Structure: Stone and reinforced concrete

Historical Background

- Ancient Origins: Believed to have been first built in the Nara period (745) by the Buddhist monk Gyōki, though historical accuracy is uncertain.

- Edo Period: Became a Kōgi-bashi (a public bridge under the Edo shogunate), playing a crucial role in Osaka’s transportation and trade. Originally a single long bridge over the Ōkawa River before Nakanoshima’s land extension.

- Meiji Era (1876): Converted into an iron bridge as part of modernization efforts. Following a great flood in 1885, the bridge was temporarily replaced by a boat bridge before being fully reconstructed.

- Taishō Era (1915): Rebuilt in its current form to accommodate the Sakai-suji tramline and enhance the aesthetics of Nakanoshima Park.

Architectural Features

- Lion Statues:

- Created by sculptor Kin’ichi Amaoka

- Four stone lions (two pairs) placed atop the bridge’s main pillars, symbolizing protection and strength.

- Unique A-un arrangement: Unlike traditional guardian statues, the open-mouthed (A-gyō) and closed-mouthed (Un-gyō) lions are positioned in reverse order.

- A fifth lion statue exists in Wakayama, owned by a merchant who made his fortune in Osaka.

- Design & Ornamentation:

- Osaka city emblem engraved on the parapets

- Elegant stone staircases leading to Nakanoshima Park

- Bronze lampposts (originally lost in wartime, restored in 1985)

- High arch structure (originally designed to accommodate boats and limit cart traffic)

Modern Preservation & Recognition

- 1972: Major restoration work carried out while preserving the original appearance.

- 1985: The ornate bronze lampposts were restored, further enhancing the bridge’s historical charm.

Cultural Significance

- One of Osaka’s Three Great Bridges (Naniwa Sandai-bashi), along with Tenjin Bridge and Tenma Bridge.

- A well-known landmark and a popular sightseeing spot, often called the “Lion Bridge” by locals.

- Offers scenic views of Nakanoshima and the Ōkawa River, making it a favored spot for cherry blossom viewing, moon gazing, and firework displays.

Conclusion

Naniwa Bridge is not just an important historical and functional bridge, but also a symbol of Osaka’s heritage, blending transportation, art, and urban beauty.

Naniwa Bridge Overview

- Bridge Length: 189.65 meters

- Width: 21.80 meters

- Structure Type: Girder Bridge (Continuous Girder) & Arch Bridge

- Completion: Taishō 4 (1915) (Reconstructed in Shōwa 50 (1975))

- Administrative Districts: Kita Ward, Chuo Ward (Osaka City)

- Crosses: Tosabori River, Dōjima River

- Access: Directly next to Kita-Hama Station (Osaka Metro Sakai-suji Line & Keihan Main Line)

A historically and architecturally significant bridge, Naniwa Bridge is not only a crucial transportation route but also a landmark symbolizing Osaka’s history and urban development.