Osaka’s Shinmachi Bridge and Its Surroundings

Shinmachi Bridge (Photographed in September 2021)

Shinmachi Bridge【Nishi Ward, Osaka City】

Contents

- 1 Osaka’s Shinmachi: On Par with Edo’s Yoshiwara and Kyoto’s Shimabara

- 2 Shinmachi Bridge in the Edo Period

- 3 Shinmachi on Historical Maps

- 4 Shinmachi Bridge: The Eastern Gateway to the Pleasure District

- 5 Shinmachi’s Layout and the Role of Shinmachi Bridge

- 6 Junkeimachi Evening Market (Chūō-ku, Minamisemba 4-chome)

- 7 Shinmachi Bridge in the Meiji Era

- 8 Shinmachi Bridge in the Shōwa Era

- 9 Overview of Shinmachi Bridge

- 10 Shinmachi Bridge and Its Surroundings

Osaka’s Shinmachi: On Par with Edo’s Yoshiwara and Kyoto’s Shimabara

Edo’s Yoshiwara and Kyoto’s Shimabara are well-known as historic pleasure districts. Alongside these two, Osaka had Shinmachi, another prestigious entertainment quarter.

Today, Shinmachi is a bustling business district filled with small and medium-sized companies, with no visible traces of its past. However, during the Edo period, it was a thriving high-class entertainment district.

To improve access to Shinmachi, Shinmachi Bridge was built as an eastern gateway to the area.

Shinmachi Bridge in the Edo Period

“Shinmachi Iron Bridge from the New Famous Places of Osaka”

(Painting by Hasegawa Sadanobu II, Collection of Kobe City Museum)

Since Shinmachi Bridge was constructed to serve the pleasure district, let’s first take a brief look at the history of Shinmachi Yukaku.

Before Shinmachi Yukaku was established, brothels were scattered throughout the city. These establishments were originally authorized by Toyotomi Hideyoshi during the construction of Osaka Castle in 1583 (Tensho 11), primarily to serve the samurai who had gathered from various regions.

When the Edo period began, Matsudaira Tadaaki was appointed as the lord of Osaka Castle. Under orders from the second shogun, Tokugawa Hidetada, he was tasked with reconstructing the castle.

During this period, a man named Kimura Matajirō petitioned for the continuation of the pleasure quarters. Matsudaira granted permission, but under one condition—all of the scattered brothels had to be consolidated into a single designated area.

As a result, Kimura selected a rural area on the outskirts of the city, developed the land, and established a new town dedicated to the pleasure district.

Thus, Shinmachi (“New Town”) was born—a name that, if anything, is as straightforward as it gets.

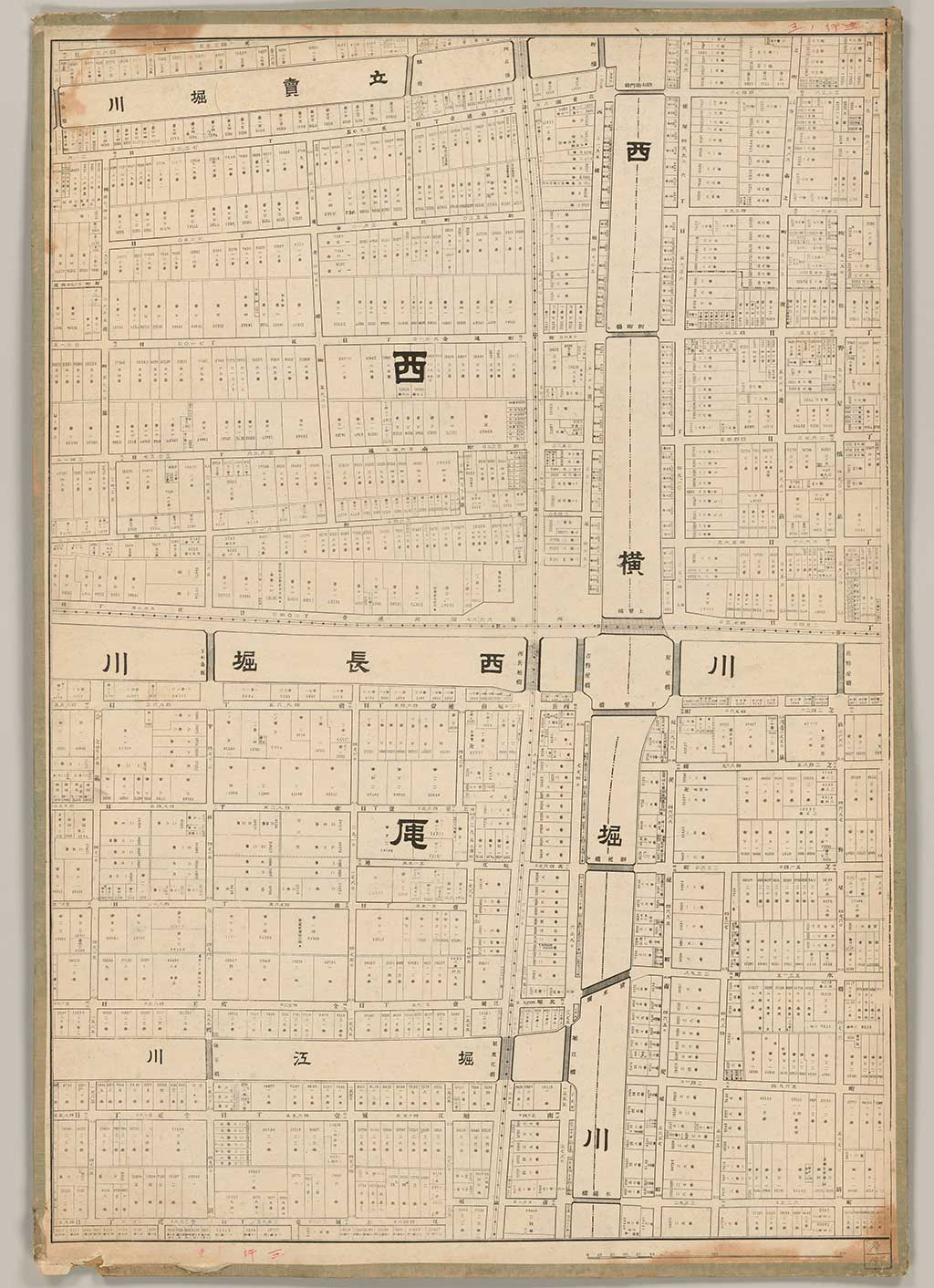

Shinmachi on Historical Maps

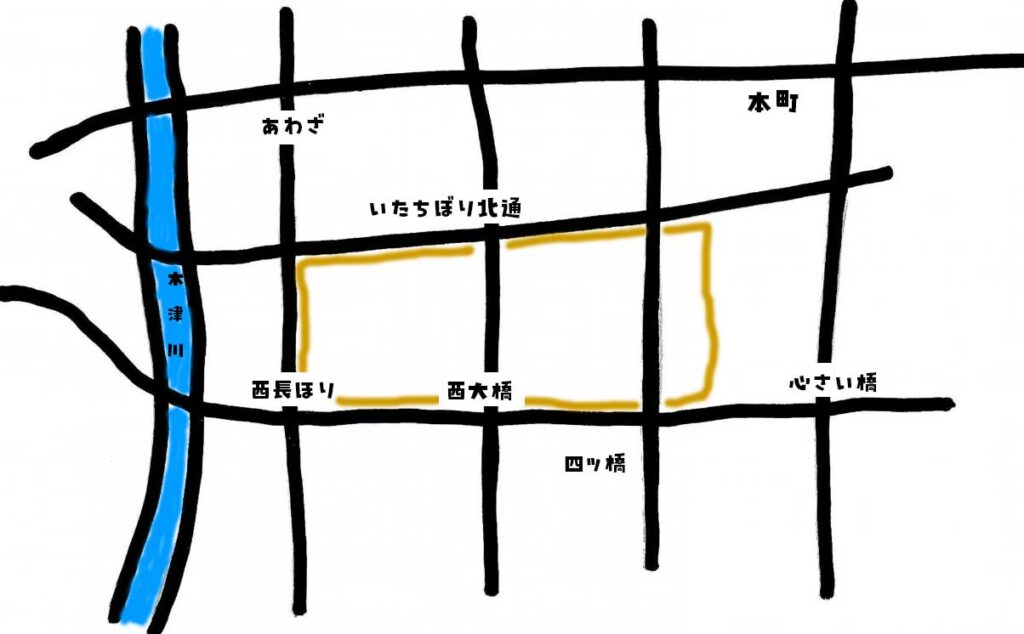

Shinmachi Yukaku was officially established in 1630 (Kan’ei 7). It was a self-contained district, surrounded by four rivers:

- Nishiyokobori River to the east

- Kizugawa River to the west

- Itaibori River to the north

- Nagahori River to the south

Today, only Kizugawa River remains. The other three rivers have been replaced by modern infrastructure:

- Nishiyokobori River → Hanshin Expressway Loop Line (running just east of Yotsubashi Avenue)

- Nagahori River → Nagahori Street

- Itaibori River → Itaibori Street

If you trace these roads on a map, you can clearly see the original borders of the former Shinmachi Yukaku.

The area outlined in yellow is believed to be the former site of the Shinmachi Yukaku. The top is north, and the bottom is south.

Shinmachi Bridge: The Eastern Gateway to the Pleasure District

The eastern entrance of Shinmachi was essentially the main gate for customers coming from the city center.

Originally, access to the district was limited to the western entrance, which faced the port. However, when an eastern gate was opened, it significantly boosted the prosperity of Shinmachi Yukaku. In this sense, Shinmachi Bridge became the foundation of that success.

Why was there only one entrance at first?

Simply put, it was to prevent courtesans from escaping—a rather harsh reality of the time.

However, having only one gate was highly inconvenient for customers, so a second entrance was established, and Shinmachi Bridge was built to improve access.

The eastern and western gates of Shinmachi were closed at 9:00 PM, after which no one was allowed to enter or leave. (Later, the curfew was extended to 11:00 PM.)

This strict regulation made Shinmachi Yukaku a completely isolated world. However, the inability to escape also meant that when an emergency arose, people were trapped inside.

Several fires broke out in Shinmachi Yukaku over the years, and with only two gates, evacuation was difficult, resulting in heavy casualties.

In response, additional emergency gates were installed. However, despite these changes, Shinmachi Bridge remained the busiest and most prominent entrance to the district.

The new emergency gates were never opened except during fires and were called “Clam Gates” (Hamago-mon).

Like a clam that remains tightly shut but opens when heated, these gates were only unsealed in case of fire—a rather bleak reality.

Shinmachi’s Layout and the Role of Shinmachi Bridge

Shinmachi consisted of five districts:

- Hyōtanmachi

- Sadoshimamachi

- Yoshiwaramachi

- Shinkyōbashimachi

- Shinhorimachi

These were collectively known as the “Five Wards” (Gokuruwa).

Shinmachi Bridge was located in Hyōtanmachi, which is why it was also known as “Hyōtanbashi” (Gourd Bridge).

Now, let’s finally return to Shinmachi Bridge itself.

Crossing Shinmachi Bridge from the east, visitors would reach the eastern gate of Shinmachi Yukaku. The bridge’s eastern side was directly connected to the bustling entertainment districts of Dotonbori and Shinsaibashi, making it a vital access point for the pleasure quarter.

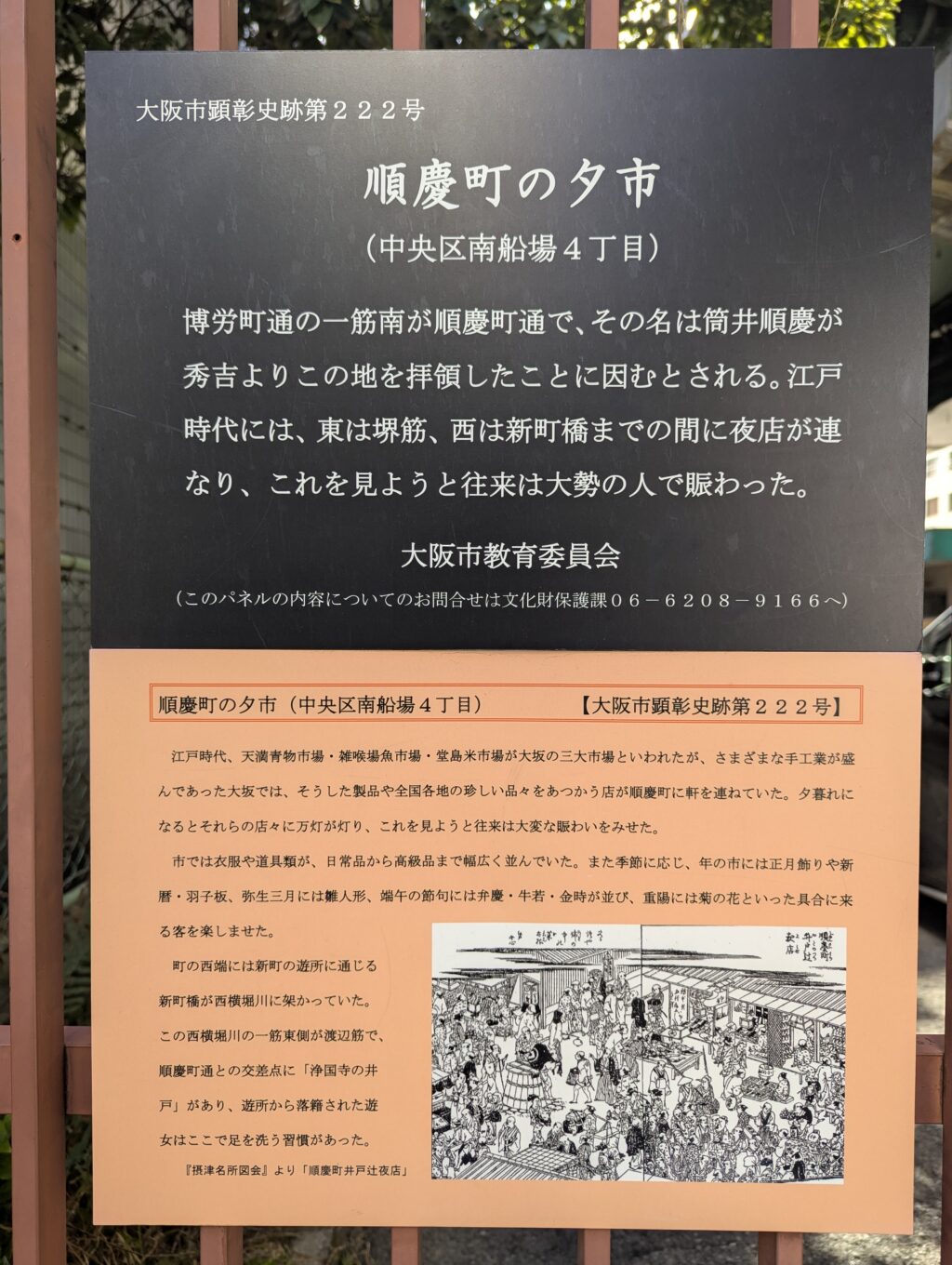

Junkeimachi Evening Market (Chūō-ku, Minamisemba 4-chome)

Shinmachi Bridge, surrounded by bustling districts, was itself a lively place. Even at night, rows of street stalls lined the bridge, creating a vibrant atmosphere.

Junkeimachi Evening Market

Junkemachi Street runs one block south of Bakurōmachi Street. Its name originates from Tsutsui Junkē, who received this land from Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

During the Edo period, the market stretched from Sakai-suji in the east to Shinmachi Bridge in the west, and it became a popular attraction, drawing large crowds of visitors eager to explore its many night stalls.

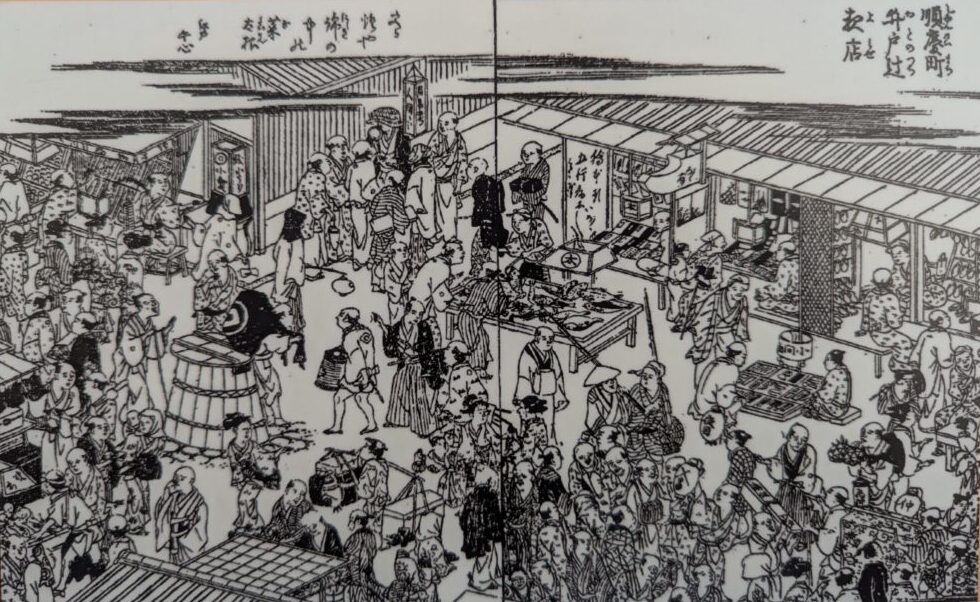

“Junkeimachi Well-Corner Night Market” from Settsu Meisho Zue

During the Edo period, Tenma Vegetable Market, Zakoba Fish Market, and Dōjima Rice Market were known as Osaka’s three major markets. However, Osaka was also a hub of various handicrafts, and Junkemachi became home to numerous shops selling rare goods from across Japan.

As evening fell, the market came to life, with lanterns illuminating the stalls, attracting large crowds of visitors.

The market sold a wide range of products, from daily necessities to luxury goods. Seasonal items were also popular:

- New Year’s Market featured decorations, calendars, and battledores (hagoita).

- March (Yayoi Festival) saw the sale of Hina dolls.

- May (Tango no Sekku, Boys’ Day Festival) displayed figures of Benkei, Ushiwakamaru, and Kintarō.

- Chrysanthemums were sold in September (Chōyō no Sekku, Chrysanthemum Festival).

Shinmachi Bridge as a Key Gateway

At the western end of Junkemachi, Shinmachi Bridge spanned Nishiyokobori River, connecting the market to Shinmachi Yukaku.

Just one street east of the river ran Watanabe-suji, where it intersected with Junkemachi Street. At this intersection stood Jōkokuji Temple’s Well, where courtesans who had left the pleasure district would traditionally wash their feet before stepping into a new life.

Managing the Heavy Traffic on Shinmachi Bridge

The night market alternated its location—on the north side of the bridge one day, and the south side the next. This was a strategic measure to distribute the weight evenly and prevent one side of the bridge from deteriorating faster than the other.

The sheer volume of foot traffic was so immense that if the stalls remained in a fixed position, it would cause uneven stress on the bridge, leading to faster wear and tear.

It wasn’t just the weight of the stalls that put pressure on the bridge, but the constant movement of people that created an imbalance. The fact that this issue had to be addressed speaks to just how crowded the area was.

At the time, Shinmachi Bridge measured approximately 33 meters in length and 3 meters in width. Illustrations from Settsu Meisho Zue depict the bridge completely packed with people, spilling onto both riverbanks—showcasing its immense popularity.

Shinmachi Bridge in the Meiji Era

Shinmachi Bridge was converted into an iron bridge in 1872 (Meiji 5), making it the second iron bridge in Osaka, following Koraibashi, which was the first in 1870 (Meiji 3).

The new Shinmachi Bridge was likely an imported cast-iron arch bridge, with wooden components above the arch structure.

The Shinmachi Bridge was constructed using a combination of wood and cast iron. The structural elements included:

- Hijiki (肘木) – Horizontal beams placed atop pillars to support the bridge deck and eaves.

- Sasuragi (簓木) – Crossbeams that reinforced the structure.

- Wooden decking and railings – The entire upper portion of the bridge was made of wood.

Between the railing posts, X-shaped wooden braces were inserted, a design commonly used at the time. Similar architectural details could be seen on Tokyo’s Nihonbashi and Ryōgokubashi, indicating a stylistic trend in Meiji-era bridge construction.

However, the steep arch of the bridge made it difficult to cross, leading to a major renovation just three years later. The sasuragi (crossbeams) were lowered and integrated with the hijiki (horizontal beams), creating a gentler slope for easier passage.

Interestingly, both the crossbeams and horizontal beams were intricately decorated—a rare feature for a public roadway bridge, as such embellishments were typically reserved for garden bridges and ornamental structures.

“Shinmachi Kyūken no Sakura” (Date Unknown, Osaka Municipal Library Collection)

“Shinmachi Kyūken no Sakura” is a historical illustration or record housed in the Osaka Municipal Library, though its publication date remains unknown. The title suggests a depiction of cherry blossoms in the Shinmachi district, possibly referencing a well-known row of cherry trees near the nine main establishments (Kyūken) of Shinmachi Yukaku.

This document provides valuable insight into the scenery and cultural atmosphere of Shinmachi during its peak, offering a glimpse into the vibrant life of the area.

The Decline of Shinmachi Yukaku and the Transformation of the District

As the Meiji era progressed, the opening of the Matsushima Yukaku and the enactment of the Prostitution Abolition Edict led to a gradual decline in the popularity of Shinmachi Yukaku.

The final blow came in 1900 (Meiji 33), when a devastating fire swept through the district, destroying most of Shinmachi.

Following the disaster, the pleasure district was relocated, and the former site was redeveloped into a commercial district.

Thanks to its prime location with excellent accessibility, the area attracted various businesses, including machinery and metal wholesalers, financial institutions, and other commercial enterprises.

Incidentally, the TV drama Doterai Yatsu—a series the author personally loved—was set in Itaibori, one of the neighboring districts.

Despite the dramatic transformation of the area, Shinmachi Bridge continued to serve as a vital crossing point, supporting the new kind of prosperity that had taken root in the district.

Shinmachi Bridge in the Shōwa Era

In 1926 (Shōwa 2), Shinmachi Bridge was rebuilt as a fire-resistant reinforced concrete arch bridge. The bridge was also significantly widened to 10.9 meters, improving traffic flow.

The surface of the concrete was adorned with artificial granite, giving the bridge a bright and elegant appearance.

“Shinmachi Bridge First Crossing Ceremony” (Published in 1927, by Kusaka Fukuzō, Osaka Municipal Central Library Collection)

“Shinmachi Bridge First Crossing Ceremony” (Published in 1927, by Kusaka Fukuzō, Osaka Municipal Central Library Collection)

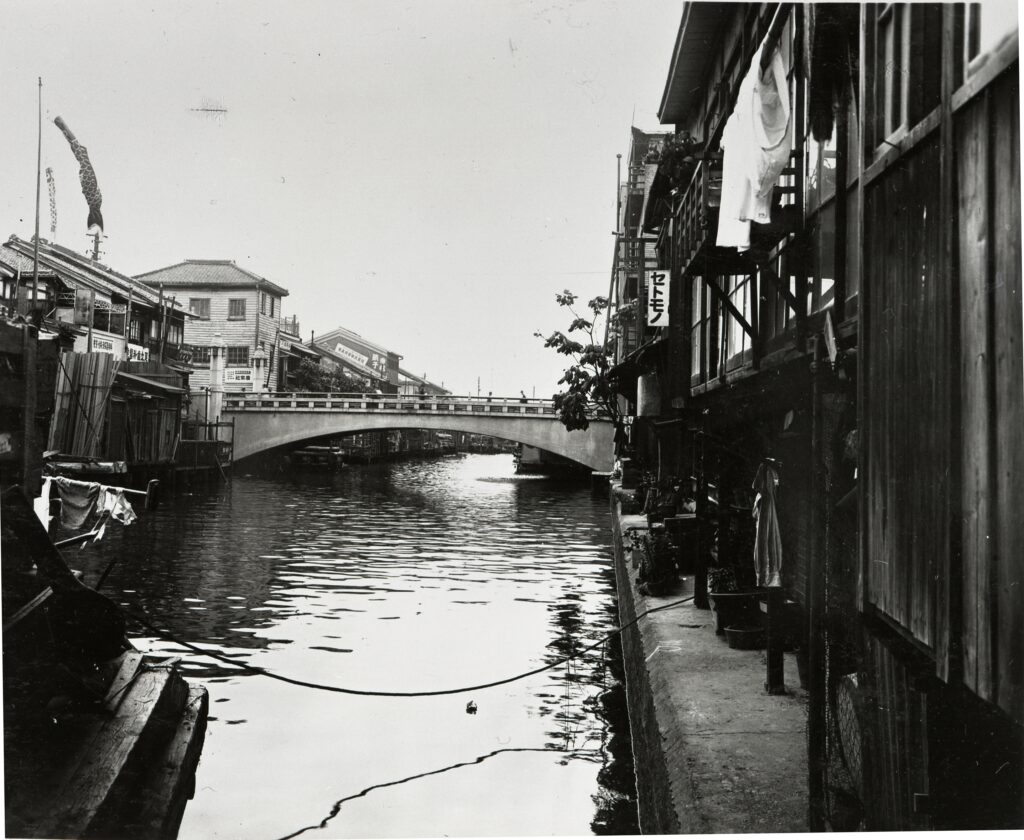

Shinmachi Bridge – The 15th Bridge on Nishiyokobori River (Photographed in August 1937, Osaka Municipal Central Library Collection)

Shinmachi Bridge – The 15th Bridge on Nishiyokobori River (Photographed in August 1937, Osaka Municipal Central Library Collection)

The photograph was taken looking south from the north (upstream), providing a clear view of Shinmachi Bridge and its surroundings.

Originally, Shinmachi Bridge was petitioned for and approved in 1672 (Kanbun 12) by the residents of Shinmachi Yukaku, serving as a crucial connection to its eastern main gate. The bridge spanned Nishiyokobori River, with its eastern end located in Minamisemba 4-chome and its western end in Shinmachi 1-chome.

After centuries of history, Shinmachi Bridge was finally decommissioned and filled in December 1971 (Shōwa 46).

Today, the Hanshin Expressway runs over the former location of the bridge, leaving only its legacy in Osaka’s history.

Overview of Shinmachi Bridge

The Shinmachi district, once home to the Shinmachi Yukaku (pleasure district), is located north of Nishi-Ōhashi Station and Nishi-Nagahori Station on the Osaka Metro Nagahori Tsurumi-ryokuchi Line.

The eastern edge of Shinmachi is near Yotsubashi Station on the Osaka Metro Yotsubashi Line.

Shinmachi Bridge and Its Surroundings

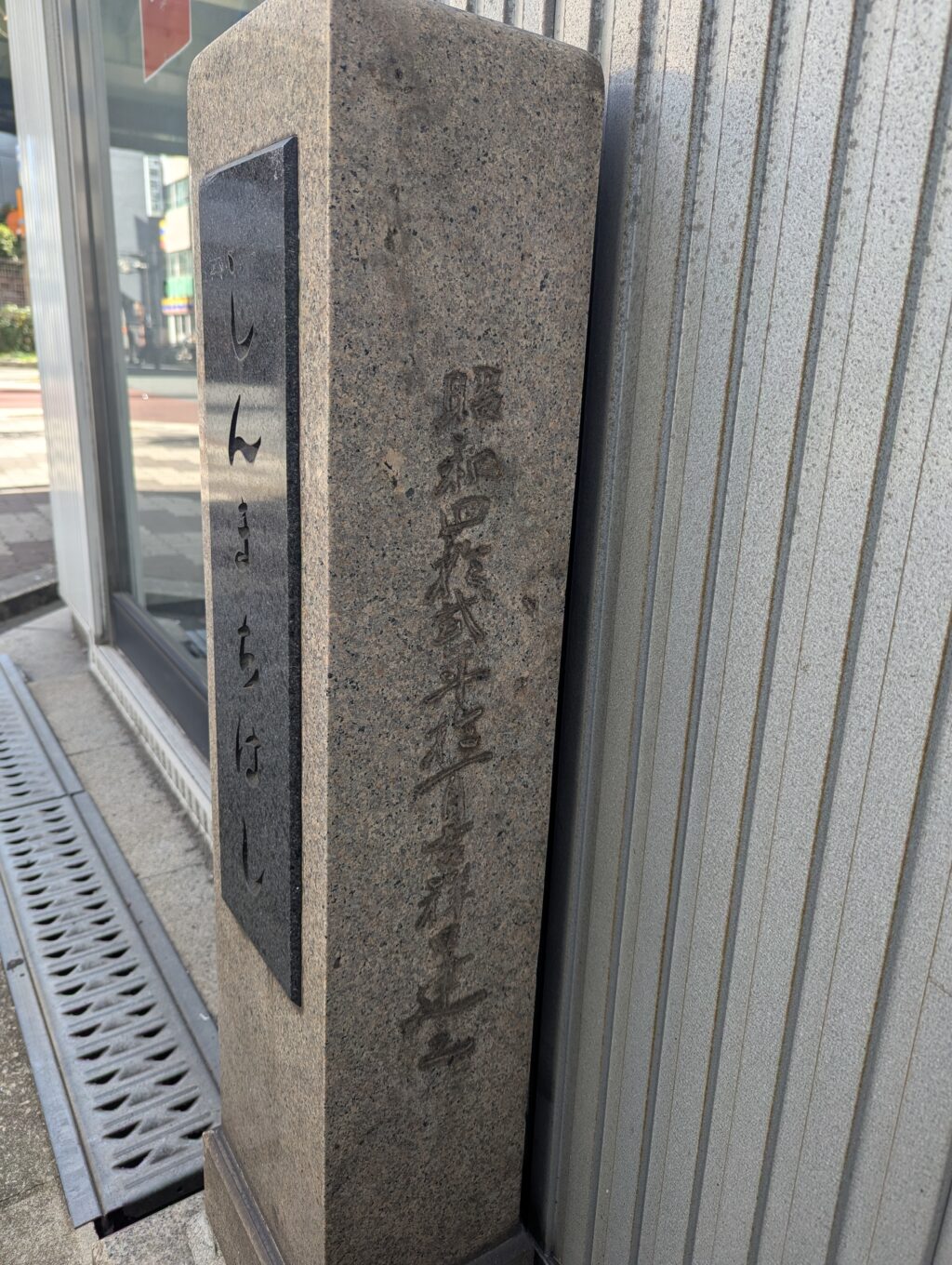

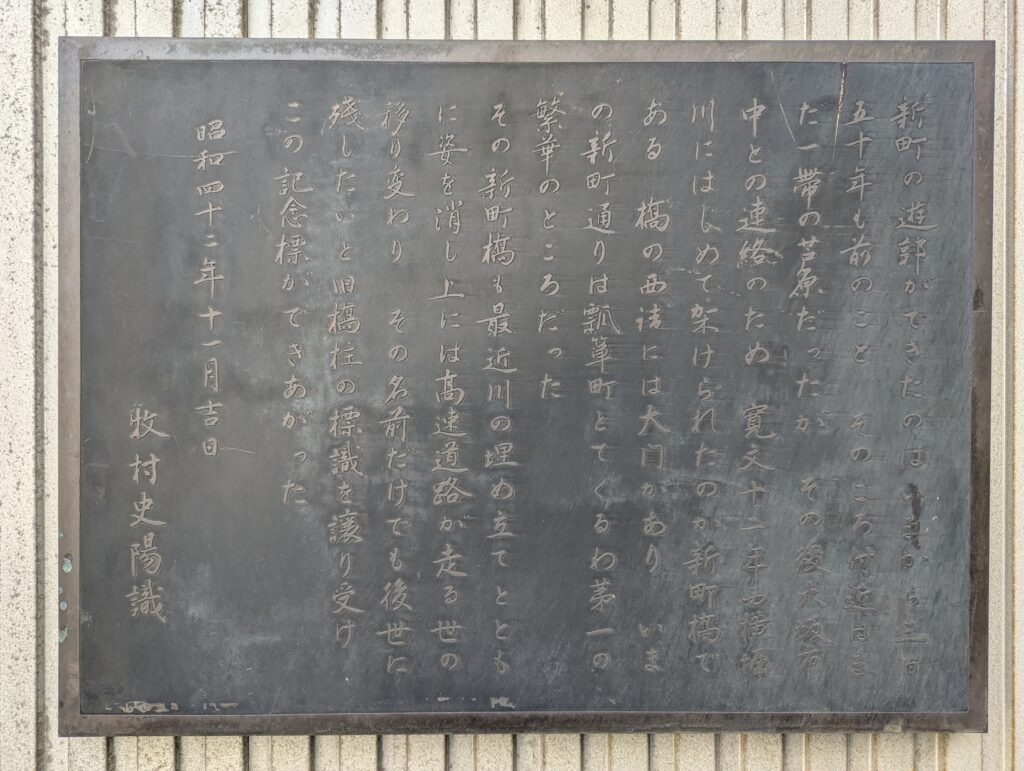

Shinmachi Bridge Commemorative Marker (Located on the east side of Yotsubashi-suji Avenue)

A commemorative marker stands as a reminder of Shinmachi Bridge’s historical significance.

This marker was created using a sign from one of the original bridge pillars, serving as a tribute to the legacy of Shinmachi Bridge.

On the western corner of the former bridge site, a modest memorial quietly stands, preserving the memory of Shinmachi Bridge in the modern cityscape.

The Shinmachi Yukaku was established over 350 years ago. At that time, the surrounding area was a vast reed field, but as the district grew, the need for better connections to Osaka’s central city led to the construction of Shinmachi Bridge over Nishiyokobori River in 1672 (Kanbun 12).

The western end of the bridge led to the main gate of the pleasure district, and what is now Shinmachi Street was once known as Hyōtanmachi, the busiest part of the district.

However, over time, Shinmachi Bridge disappeared as the river was filled in, and today, the Hanshin Expressway runs over its former location.

To preserve its historical significance, a commemorative marker was created using a sign from one of the original bridge pillars, ensuring that the name of Shinmachi Bridge would not be forgotten.

Dated November 1967 (Shōwa 42), Inscribed by Makimura Shiyō (Cited from the explanatory plaque).

A Striking Modern Landmark: Nagase Sangyo Osaka Headquarters Building (Yotsubashi-suji)

The Nagase Sangyo Osaka Headquarters Building stands out as a remarkable modern structure along Yotsubashi-suji Avenue.

This historical yet modern building continues to be a prominent feature of the area, blending Osaka’s commercial heritage with contemporary architecture.

Organic Building: Headquarters of Oguraya Yamamoto (Minamisemba 4-chome)

The Organic Building, completed in 1993, serves as the headquarters of Oguraya Yamamoto, a long-established konbu (kelp) merchant.

This uniquely designed building was created by Italian architect Gaetano Pesce, featuring a distinctive, organic-inspired aesthetic that sets it apart from traditional architecture in Osaka.