Tenjinbashi: A Bridge with a Rich History in Osaka

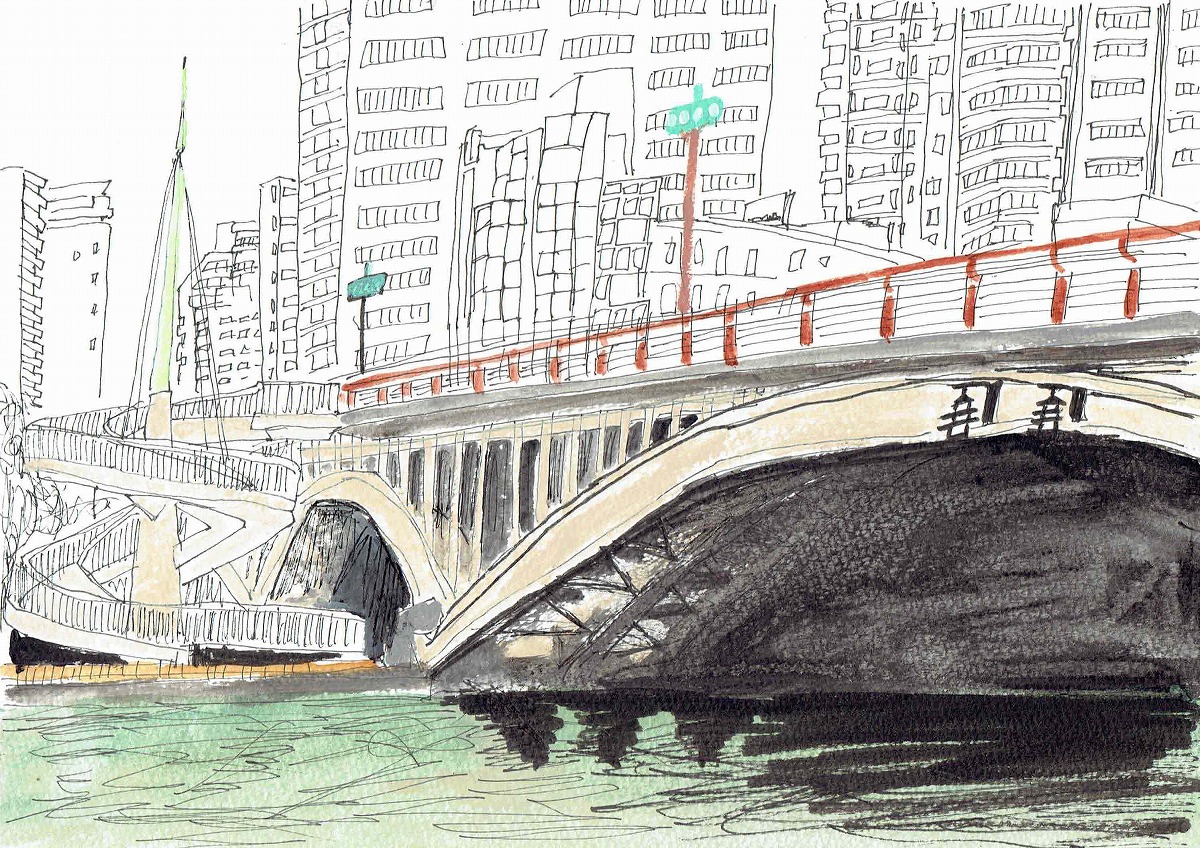

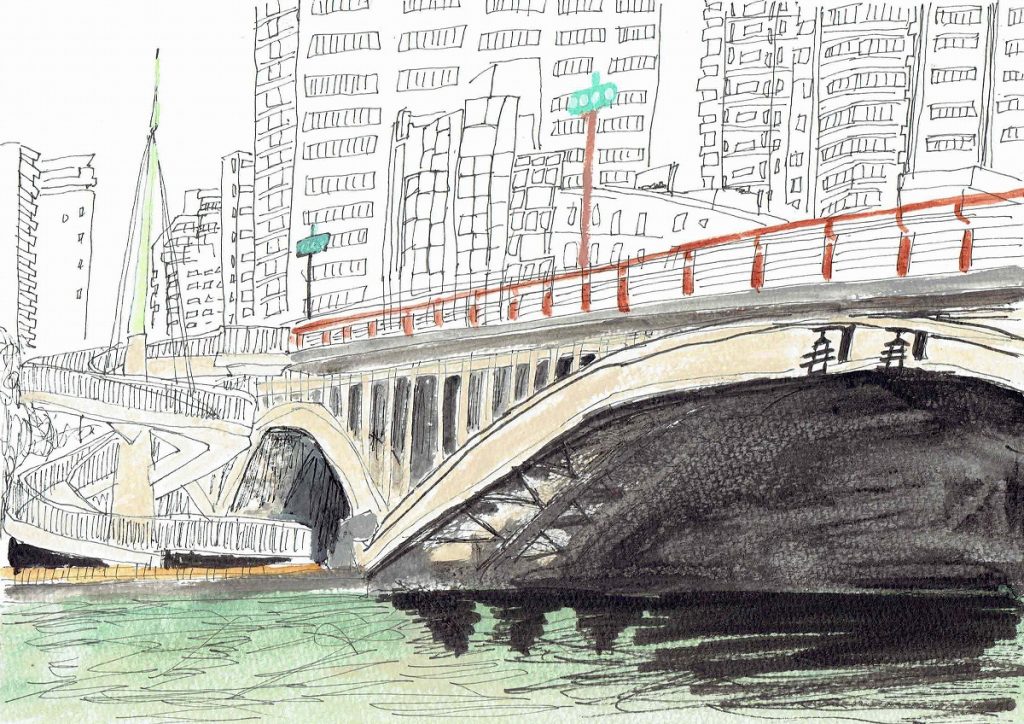

Illustration by Hiroki Fujimoto

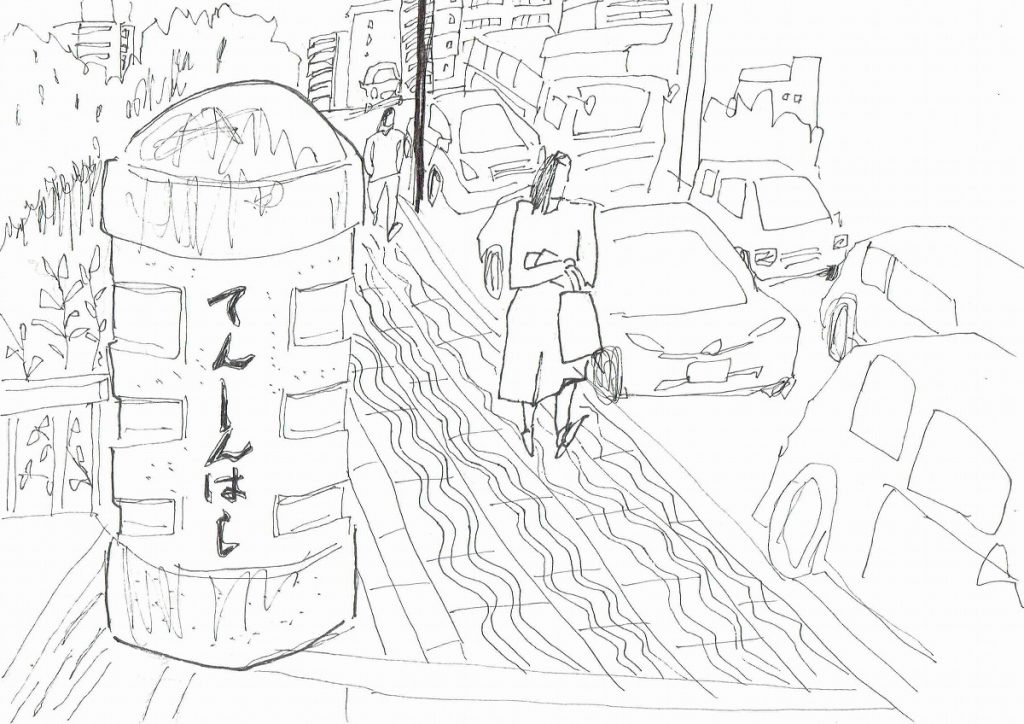

Tenjinbashi [Kita Ward, Osaka City]

Contents

Tenjinbashi: A Bridge with a Rich History in Osaka

Tenjinbashi is an important bridge in the heart of Osaka, connecting the Uemachi Plateau with the northern side of the Ōkawa River. During the Edo period, it was known as one of the “Three Great Bridges of Naniwa” alongside Tenmabashi and Naniwabashi. Among them, Tenjinbashi stood out for its remarkable length.

In the Jōkyō era (1684-1688), flood control work on the Yodo River widened the river, extending the bridge to approximately 250 meters. At that time, Tenjinbashi was built with a steep arch, reaching a height of about 4.5 meters. This design not only allowed boats to pass underneath but also served to limit vehicular traffic, which helped maintain the bridge’s durability.

However, as a wooden bridge, Tenjinbashi suffered repeated damage from floods and fires. Historical records show that in 1724 (Kyōhō 9), a major fire known as the “Myōchi Fire” destroyed 58 spans of the bridge’s total 122 spans. Over the 200 years from 1686 (Jōkyō 3) to 1888 (Meiji 21), when the bridge was replaced with an iron structure, Tenjinbashi was rebuilt or repaired at least 13 times.

Maintaining the bridge was a constant challenge. Measures such as prohibiting horses, cattle, and carts from crossing were introduced to preserve its structure. Additionally, in 1767 (Meiwa 4), a merchant named Tsukaguchiya Shichibei personally funded the bridge’s repairs. He cleverly used the revenue from renting out rights to operate inns, directing the profits toward maintenance costs.

With the modernization of Japan in the Meiji period, Tenjinbashi was replaced with an iron bridge. Today, it continues to serve as a crucial transportation link in Osaka while blending into the contemporary urban landscape.

Reflecting on Tenjinbashi’s history, we can see the wisdom, ingenuity, and dedication of the people who maintained it across generations. If you ever visit Osaka, take a walk across Tenjinbashi and appreciate the rich history embedded in its structure.

Medieval Period: The Origins of Tenjinbashi

It is believed that Tenjinbashi was first constructed in 1594 (Bunroku 3).

During the campaign against Ishiyama Hongan-ji in 1570 (Genki 1), Oda Nobunaga also set fire to Osaka Tenmangu Shrine and confiscated its lands. This action was taken because Omura Yuko, the shrine’s estate manager and a master of linked-verse poetry (renga), was suspected of secretly collaborating with Ishiyama Hongan-ji.

However, in the era of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, Yuko later became part of the renga circle that frequented Osaka Castle. In 1594 (Bunroku 3), he wrote the Noh play Yoshino Mode and was rewarded by Hideyoshi. Grateful for this recognition, Yuko petitioned for the restoration of Osaka Tenmangu’s lands. The shrine officials, in turn, wished to express their gratitude to Yuko, but he declined any personal rewards. Instead, he requested the construction of a new bridge over the Ōkawa River. This is said to be how Tenjinbashi was built.

Initially, the bridge had no formal name and was simply called the “New Bridge” (Shinbashi). Over time, as it came under the management of Osaka Tenmangu Shrine, it gradually became known as Tenjinbashi.

Edo Period: The Significance and Challenges of Tenjinbashi

In 1616 (Genna 2), Osaka came under Tokugawa rule. Around the same time, a system of town organizations known as Osaka Sangō was established, and the management of Tenjinbashi was assigned to Tenma-gumi, one of these town groups. This meant that the bridge was originally maintained by the local residents.

However, due to Tenjinbashi’s increasing importance as a key transportation route connecting the Uemachi Plateau and the northern Ōkawa River, it was later designated as a public bridge (Kōgi-bashi) under the direct control of the shogunate.

A Vital Transportation Link and Its Growing Importance

As people traveled more frequently across the bridge, the surrounding area flourished, further enhancing Tenjinbashi’s significance. This growing importance led to its official recognition as a public bridge. One event that highlights this status is the grand bridge-rebuilding ceremony in 1850 (Kaei 3). According to the Settsu Meisho Zue Taisei, the ceremony was conducted in a solemn manner, with curtains draped along the railings, offerings placed on ritual trays, and sacred Shinto paper streamers (heihaku) displayed. Officials from both the eastern and western parts of Osaka also attended, underscoring the bridge’s status as a vital structure.

Even in times of conflict, Tenjinbashi played a crucial role. During Ōshio Heihachirō’s Rebellion in 1837 (Tenpō 8), the shogunate swiftly destroyed parts of Tenjinbashi to prevent the rebel forces from advancing. This incident is detailed in Mori Ōgai’s novel Ōshio Heihachirō.

Together with Tenmabashi and Naniwabashi, Tenjinbashi was one of the Three Great Bridges of Osaka, and among them, it was the longest. During flood control work on the Yodo River in the Jōkyō era, the river was widened, extending Tenjinbashi to approximately 250 meters. This is believed to have been its longest recorded length. Interestingly, while Tenjinbashi was the longest, Tenmabashi was about 1 meter wider. The bridge also had a steep arch of about 4.5 meters, making it quite a challenge to cross.

Disasters and Reconstruction Efforts

Due to its location in a city with numerous rivers, Tenjinbashi was frequently damaged by floods and fires. The most devastating fire in Osaka’s history, the Myōchi Fire of 1724 (Kyōhō 9), burned down 58 spans out of the bridge’s total 122 spans. This fire also damaged 9 out of the 12 public bridges in Osaka, highlighting the scale of the disaster.

In terms of flood damage, Tenjinbashi was reconstructed at least 13 times between 1686 (Jōkyō 3) and 1888 (Meiji 21), when it was finally replaced with an iron bridge.

Maintenance Challenges and Funding Innovations

Even without disasters, wooden bridges were inherently fragile compared to iron bridges, making maintenance a constant struggle. Various measures were taken to reduce wear and tear, including:

- Banning horses, cattle, and carts from crossing.

- Prohibiting street vendors from setting up stalls on the bridge.

- Restricting the size of handcarts (bekakuruma), which became widely used in the mid-Edo period, to reduce strain on the structure.

Funding repairs was another challenge. Initially, repair costs were covered by the Osaka Treasury (Ōsaka Kinzō). However, in 1767 (Meiwa 4), a merchant named Tsukaguchiya Shichibee took on the responsibility of securing funds. His innovative idea was to lease operating rights for 300 inns, charging a monthly fee of 15 momme of silver per inn, with the collected money going toward bridge repairs. The shogunate approved this proposal, and Shichibee managed 11 of Osaka’s 12 public bridges, excluding Shiginobashi. To further ease the financial burden on lessees, he adjusted the system by increasing the number of shares while reducing individual fees and even loaned money to the shogunate, using the interest for maintenance costs.

Structural Safety and a Tragic Incident

Ensuring the bridge’s structural integrity was not just a financial matter but also a safety concern. In 1832 (Tenpō 3), during the Tenjin Festival, part of Tenjinbashi collapsed when a large festival float from the Tenma Market was carried across. Tragically, this accident resulted in 13 deaths.

Through floods, fires, financial struggles, and even war, Tenjinbashi remained an essential lifeline for Osaka. The challenges faced by the bridge reflect the resilience and ingenuity of those who maintained it, ensuring its role as one of the city’s most vital connections.

From the Meiji Era Onward: The Modernization of Tenjinbashi

Tenjinbashi in the Meiji Era (From the Collection of Osaka Municipal Central Library)

Tenjinbashi in the Meiji Era (From the Collection of Osaka Municipal Central Library)

Tenjinbashi (Meiji 2 – Shōwa 6)

The Shift from Wooden to Iron Bridges

Maintaining wooden bridges had always been a significant challenge, and with the arrival of the Meiji era, they were gradually replaced with iron bridges. This transition was greatly accelerated by the Great Flood of 1885 (Meiji 18).

Starting in early June, heavy rain continued for nearly two weeks, causing the Yodo River embankment in Hirakata to collapse. This resulted in widespread flooding across the Kawachi Plain in eastern Osaka. In a desperate attempt to drain the water, officials even intentionally breached the embankment near Sakuranomiya, an extreme measure taken to mitigate further damage.

Before these collapsed embankments could be fully repaired, another heavy downpour struck in late June. One by one, bridges along the Yodo River were swept away, flooding nearly the entire city of Osaka. The destruction of these bridges paralyzed transportation, significantly delaying restoration efforts.

The Push for Iron Bridges

In response to this crisis, Osaka’s Governor Tateno Gōzō proposed the conversion of 18 major city bridges into iron bridges. However, due to budget constraints, it was impossible to replace all of them at once. Instead, the first five bridges to be converted were:

- Tenjinbashi

- Tenmabashi

- Higobashi

- Watanabebashi

- Kizugawabashi

The reconstruction of Tenjinbashi relied primarily on imported materials from Germany. However, some components, such as the iron railings and the decorative bridge nameplate, were domestically manufactured by Kawasaki Shipyard.

This marked a new era in the modernization of Osaka’s infrastructure, as Tenjinbashi transitioned from a historically significant but fragile wooden structure into a durable iron bridge, capable of withstanding the challenges of the rapidly developing city.

The Present-Day Tenjinbashi

Illustration by Hiroki Fujimoto

The current Tenjinbashi was reconstructed as part of the First Urban Planning Project. Construction began in 1931 (Shōwa 6), in conjunction with the expansion of the Matsuyamachi-suji Line, and it took approximately three years to complete.

Initially, a concrete arch bridge was planned, but due to ground stability issues, the design was changed to a steel arch bridge just before construction began.

Tenjinbashi (Completed in Shōwa 9, 1934)

In 1987 (Shōwa 62), a spiral ramp was added to the bridge. Additionally, ceramic panels depicting the Kentōshi (Japanese envoy ships to Tang China) and scenes from the Tenjin Festival Picture Scroll were installed as decorative elements.

Illustration by Hiroki Fujimoto

Overview of Tenjinbashi

- Bridge Length: 210.70 m

- Width: 22.00 m

- Structure Type: Arch Bridge (Two-Hinged Arch)

- Completion: Shōwa 9 (1934)

- Administrative Districts: Kita Ward, Chūō Ward

- Rivers: Dōjima River (Former Yodo River), Tosabori River

Tenjinbashi spans the Ōkawa River, passing through the eastern tip of Nakanoshima.